by W.H. Fuller from his book "Small-bore target Shooting" - 1963

This extract is probably one of the most comprehensive, carefully considered and researched pieces ever published on the subject.

It is a MUST read for anyone experiencing difficulties such as 'shot-stringing', 'two-group diagrams' and other inconsistent results.

You may suspect this would now be a dated assessment but, with a very few obvious exceptions, the information is as relevant today as it ever was!

THE small-bore marksman should understand that technically there never can be

a perfect result, either in practice or in theory. No combination of rifle,

ammunition and rifleman can put ten consecutive shots through one hole, the

size of that of a single bullet. The target will always reveal, by enlargement

of the hole, deviations from perfect accuracy.

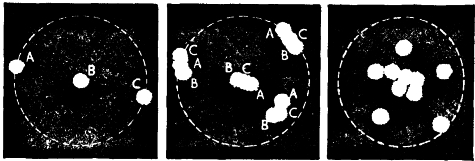

Fig.1 : A …….....................…..B

Ten Shots Thro' One Hole

A) - The impossible "ten shots through one hole"-where it would appear that only one shot has passed through the target.

B) - The possible "ten shots in one hole". A few authentic groups of this size have been shot during the past few years, not invariable by top flight marksmen.

However, "flash" results might appear to negative

the facts. For example, every marksman will at some time fire two shots in a

string of ten which will pass through the same hole. At rare intervals, a few

marksmen will fire two consecutive shots which will do the same thing.

Rifle and ammunition have compensatory effects and faults in one are corrected

often by recoil, jump and flip. However, from averages of leading marksmen through

the years, it is known that the marksman is not as yet, the weakest link in

the chain. If the two mechanical factors were so improved that half-inch groups

were a matter of course, many marksmen would be able to shoot to that standard.

Further, an expert rifleman can, on occasion, shoot to a standard as high as

can be achieved from a test-bed, but whereas a test-bed is likely to maintain

its performance indefinitely, the marksman will not. Inversely, test shooting

from a test-bed will not always improve on results obtained by a good shooter

in tip-top form.

Rifle and ammunition will produce groups of specific size and shape. Errors

of the riflemen will produce groups of varying size and shape. Sometimes a combination

will produce a larger group. Sometimes when compensation is consistent a smaller

group may result. But a group of some size will always be formed.

Fig.2 : A……………………………B………………………….C

Laws of Chance and Grouping

A - Certainty. Every shot will certainly fall inside the diameter of the group of which a combination is capable.

B - Indeterminacy. But the shots (A, B, C) may fall anywhere inside that diameter and in any order. Where, is indeterminable.

C- Probability. It is probable that more shots will fall towards the centre than away from it.

The distribution of shots within the group is, however, subject

to chance. Although the reasons for inaccuracies may be causal, they have to

be considered as casual, because there is little to be recognised to account

for the departures from accuracy and almost nothing that can be done to correct

the apparent errors. Laws of chance apply. If a combination of rifle, ammunition

and rifleman shoot regularly into a certain shape and size of group and nothing

additional interferes, then it can be stated with "certainty" that

the next shot will fall into the same group. But this law does not state where

inside the group the next shot will fall. It may drop on any one of the previous

shots, or it may drop away to the extreme limit of the group: the second law-"indeterminacy".

Such shooting can be disturbing to the rifleman who may not realize that it

is normal. A third law says that there is the "probability" that more

shots will fall towards the centre than away from it. When large showers of

projectiles are involved, the law will be seen to work, but it will not appear

to apply to the comparatively few shots on a small-bore target, although it

does do so when many TARGETS

are considered.

Chance permits strange combinations to appear almost continuously and those

which include closely grouped shots within the group are most likely to mislead.

To get two, three, or even more shots very close together, particularly successive

shots, is a result of pure chance.

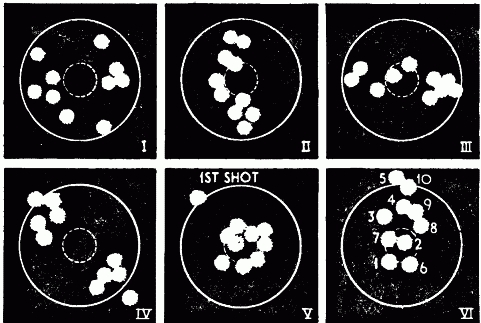

Fig.3 - Chance Effects (1)

The presence of three shots in a tight cluster in the centre of a group does not indicate a good rifle, good ammunition or good shooting. It is mere chance and although such displays are constantly occurring they should not mislead the marksman.

They are unlikely to indicate the true centre of the group, nor

are they the result of extra good shooting. Suppose a rifle and a batch of ammunition

having a two-inch group are handed to a rifleman with a two¬inch group ability.

His first shot is fired when both left-hand group limits are operative, and

it falls on the extreme left hand of a four-inch group. His second shot is fired

with both right-hand limits predominating and this shot falls four inches away

from the first. His third shot is fired on his left-hand bent, but with the

rifle selecting its right-hand limit; and his fourth shot on his right-hand

bent and the rifle on its left hand. These last two shots drop dead on top of

one another in the centre of the four-inch group, but they do not indicate good

shooting-two wrongs cannot make a right-for all four shots were cited as being

out.

The marksman then centralizes his aim for the fifth shot and the rifle-ammunition

group elects to shoot centrally also. This shot passes through the hole made

by the third and fourth shots. Because three of the five shots pass through

one hole, they are not proof of good shooting. They mean very little; the marksman

has no means of knowing why they went where they did. The only holes which indicate

anything definite are the first two, four inches apart, that fix the diameter

of the possible rifle-ammunition-rifleman group, and the actual quality of the

shooting. It follows that what happens inside the group is of no consequence;

though it can be of interest to the individual marksman, if he does not assume

that the tightest collection of shots on a target represent the true centre

of the group and a standard to which he and his equipment should always shoot.

Fig.4 - Chance Effects (2)

Key-holing of shots outside the to-ring also means very little.

Either of the two shots in the 9-ring could have fallen anywhere inside the three dotted rings, even to making good centres.

A peculiar coincidence often occurs at long-range TARGETS

.

The rifleman fires the early shots of a string into the centre. Then, for no

apparent reason, two consecutive shots appear very close together out in the

nine zone. He diagnoses a change in position as the cause; in most cases he

will be correct; but he will be inclined to think his shooting, although he

has erred in one respect, has remained good. Actually it is only chance which

has brought the two shots so very close together. Both shots could be due to

a changed group centre, the result of changed body position, or either could

be due to a temporary lapse of hold.

The criterion of the ability of a set-up to shoot lies in the size of the group

fixed by the widest spaced shots. If the size of such a group coincides with

the diameter of the 10-ring, the marksman will shoot possibles and it is obvious

that his primary object should be to shoot tight groups, which can be achieved

only if he practises group shooting for that purpose alone. Taking a few shots

for sighting a rifle before a match card is not group shooting: in fact as soon

as the sights are touched, it becomes "application" shooting. The

first requirement in group-shooting practice is to leave the sights severely

alone and to alter them only at the end of a ten-shot string in readiness for

the next.

The usefulness of any practice is not confined to the interest aroused from

card to card. It should encompass the whole aspect of practising to shoot a

normal series of cards. A marksman shooting in leagues in a club does not usually

have more than two competition cards to shoot each week, but if he enters competitions

at open meetings he finds himself committed, particularly in squadded events,

to shooting a string of four or more cards. This may quite easily strain the

ability of the club man who is used to shooting only one or two cards at a time.

Therefore, any serious group shooting should aim at getting at least four strings

of ten shots off under a seven-minute time schedule for each card, to cater

for open meeting events.

Another aspect of sight changing during practice should be considered. If a

marksman shoots a possible on a competition card without changing sights, an

ideal group has been shot, not altogether because the sights were exactly adjusted,

but because of his good shooting. It follows that the marksman who wants to

practise good shooting as distinct from scoring should leave the sights alone.

Again, if a marksman shoots possibles without sight changing, as most possibles

are shot, he could have done so without using the spotting 'scope. Discarding

the telescope during competition shooting is not advised, but in group practice

it is sound to look upon it as a liability.

The beginner, and even the experienced marksman who is practising, should set

out with three determinations in mind, at least for the first two or three 10-shot

strings: (1) to shoot strings of not less than ten shots in five or six minutes;

(2) to eschew sight changing; (3) to discard the telescope. Then the whole attention

can be given to shooting without any distractions. Any marksman who shoots consistently

to such a programme will be very surprised by the real quality of his shooting.

It may also draw his attention to reasons for faulty competition shooting, which

may not always arise out of the failings of his own gunmanship. Later, when

he finds the standard of his group shooting has improved, he can incorpor¬ate

the telescope and sight changing into his programme. The beginner, in particular,

should not use a telescope-he can always get someone to 'scope for him-until

he has reached a standard of ability and confidence.

When practising group shooting the marksman's whole attention should be given

to repeating both the same hold and the same aiming for all shots. It is disastrous

to get into the habit of blazing off the ten rounds in as short a time as possible,

thinking "it doesn't matter". Every practice round should be given

as much care as, if not more than, a round that will count on a competition

card; otherwise its value is completely lost. In addition, fast, irresponsible

shooting can easily develop careless aiming and inattentive thinking.

To ensure that the group shall give the best possible information the ten shots

should be fired at one diagram. It is not too easy to estimate the size of a

short-range group or its centre if the shots are scattered over five or ten

diagrams, and to move from one to another may involve positional troubles. True,

the shooter will have to move over when shooting competition cards, but for

his basic grouping practice it is best to shoot at one diagram.

Having shot the group, it becomes simple to change the sights to centralize

the group on the target. A suggestion may be that one or two of the worst shots

should be omitted and the group centralized on the remainder. But as these shots,

unless they are "declared out", represent his true ability and they

should be considered. The second string of shots may prove that the outsiders

are not a general expression of the shooting and could have been left out, but

the shooter is not to know this. Even then, only partial proof lies in the group

shot by the second string.

Sights cannot be set on the position of one or two shots. To try is likely to

lead to the disheartening practice known as "chasing the error", where

a marksman continually changes his sights from one shot to another, first from

one side, then the other, or up and down.

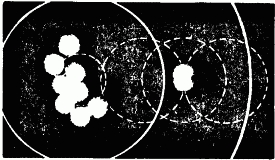

Fig.6 - Chasing the Error

A common fault, due to unnecessary fiddling with the sights.

The exercise usually includes several passes across the target before stability is reached.

As the grouping ability of the modern rifle is about one minute of angle, i.e.,

four clicks, there is little point in chasing the disposition of a shot that

might be only one click out and will always be within the group size of the

complete set-up. It is far better to fire a complete string of shots and to

reset the sights from the total evidence given.

However, in a club where practice time is at a premium and each shooter is allowed

only time to get in one practice card before his competition cards, or where

a shooter is limited by expense, the best way is to combine the grouping practice

with sight setting. Fire seven shots at one aiming-mark with as much care as

possible without the 'scope. Then reset the sights if necessary and fire the

next two or three shots at one or two other diagrams. Break down completely

after the seventh shot and then shoot the remaining shots as if starting an

entirely new string. The last three shots will indicate whether the sights did

need to be adjusted, but bear in mind that these three shots are just as likely

to exhibit the outside characteristics of your shooting as did the first seven.

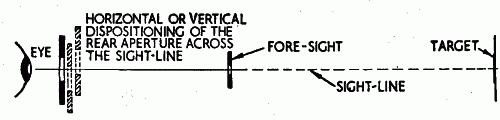

When resetting the sights the shooter's eye should follow the resetting. It

is easy, particularly for the shooter who will remain in the aim for the whole

ten shots, to move the rear-sight across the sight-line without moving the sight-line.

The target results of this error usually appear in the following manner. After

three of four shots the marksman decides, because all the shots hang on one

edge of the ten-ring, to move the sights up or over two clicks. He does this,

but the next two shots still hit the edge of the ring in the same place. He

may then wonder if he did actually put the sights on, or perhaps thinking that

the sights are not working as they should, puts two more on.

Fig.6 - Cheating the Sight-Line

It is easily possible for the rear-sight to be moved across the sight-line whilst the eye and fore-sight remain fixed. Every sight change should be accompanied by a complete breakdown of aim and even of hold.

Again the shots drop on the same spot, so he puts on two more,

shuffles his body round a little and then finds his next two shots right out

on the other side. Although the rear-sight has been moved, the eye has not followed

its course and remains in the same position as previously. Three or four clicks

mean very little when resetting the head, but they mean an inch at 100 yards.

It is always necessary after having made a sight change to break down completely

and then to rebuild the hold making sure that the eye is properly centred behind

the rear-sight aperture.

If a sight tends to show sluggishness in movement, it fails to appear to move

backwards and forwards click by click, the difficulty can be overcome, until

the sight can be sent for repair, by moving the sight five clicks to the right

and then four to the left to obtain a one-click sideways movement. This sight

fault can be due to wear on the lead screws or their mating threads, or to a

knock having jammed the slides tighter than they should be.

Having cited a few cases of group pictures by manufacturing deliberate faults

at the firing-point, it should be possible to diagnose a target group for similar

faults from the shooter's end.

Diagnosis

The shape and size of a group depends on the rifle, the rifle¬man

and the ammunition.

The rifle is the factor likely to be more constant than the other two, particularly

over a comparative short time. A poor barrel will often shoot a group having

an empty centre over a large diameter and may pack more shots in one place than

another. This could arise out of an insufficiency of shots but, if the effects

are noticeable over a series of cards, the barrel should be suspected.

A rifle that shoots an elongated group may do so for two reasons. If the ellipse

is vertical or nearly so, it can be because of variation in bullet velocity,

which may be inherent in the batch of ammunition, or, more likely, to a weak

or indifferent striker spring. If the ellipse spreads across the target, provided

wind is not responsible, it can be because of faulty bedding of the barrel in

the stock. Check the fixings, and the free move¬ment of the barrel if it

is intended to be fully floating. Examine the trough of the fore-end for bruise

and "rub" marks, where the barrel can be "tapping" the stock

when it vibrates as the rifle is fired. These small "touch" areas

should be scraped down with a tool until the barrel can move freely and fully

in all directions. With a rifle that has a pressure pad near the top end of

the fore-end (rather rare these days) make sure that it is sufficiently high

for the barrel to remain in contact with it as the barrel is stressed out from

the stock. The pressure required depends largely on the design of the rifle,

but it is usually between about three and five pounds. With a fully bedded barrel

or one with barrel clamps, be certain that the barrel remains in contact with

the fixings and that these are tight in the stock. Loose or variable fixings

are likely to change the centre of the group, but may or may not affect its

size. Check that when the barrel is stressed over in the stock it immediately

returns to its original position and does not "hang over" in the direction

to which it is stressed.

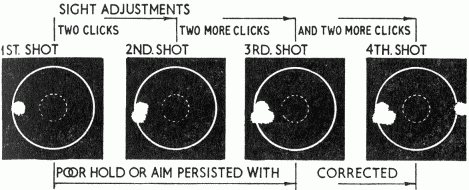

Fig.7 - Group Diagnosis (1) The Rifle

The TARGETS and groups are drawn to emphasize the distribution of shots. In practice, the groups will generally be larger but it is the shape of the group which gives the information, not the size.

I ) - Indicative of a poor barrel.

II ) - Varying ignition-weak striker-spring or damaged firing pin. The group will be vertical or nearly so.

III ) - Faulty bedding. The group may be at any angle, with one end more heavily loaded than the other.

IV ) - Loose stock fixings-two groups may form from shots in any order.

V) - Stock-barrel shift-due to recoil shock with slow recovery, or to temperature effects: again faulty bedding.

VI ) - Leading. Each successive shot will climb a little higher, then drop back into the centre and the sequence be repeated. The sketch shows two equal shot cycles, but in practice, the number of shots to complete any cycle is unpredictable.

A rifle that "always" puts its first shot out and

then continues to shoot like clockwork can be affected by stock-barrel temperature,

from stock-barrel shift, or by shock shift. The first fault may be the result

of insecure bedding or be the result of inadequate curing of the timber, or

by a shake fault; the second, by partially loose fixings and the third by fixings

which are affected by sling stresses. There is little that can be done with

an uncured or straked stock and scrapping is the only real answer. If the stock

is free of shakes, remove it from the barrel and keep it in a warm airing-cupboard

for two or three weeks. Then re-bed the barrel correctly in all respects. Shock

shift is usually caused by weak fixings allowing the sling to stress the barrel

to one side after the first shot. When the rifle is rested after shooting, the

barrel eases its way back to its original position.

A rifle that changes its group centre or size suddenly during the course of

a shoot is almost certain to be suffering from a loose and, therefore changing

fixing, affecting another fixing. This is most likely to be in the rifle, but

it could be due to sling fittings sliding into or out of position.

A rifle that allows the shots to creep gradually out of the 10-ring for, perhaps,

four or five shots and then suddenly drops back again and repeats this, has

leading trouble, which can sometimes be cured by a thorough scouring. If a barrel

leads up repeatedly, then, although it may shoot excellent groups. when free

of it, it should be discarded for continuously high level shooting. Leading

is likely to occur without warning and regular cleaning will not always eliminate

the fault in time.

Some rifles appear to need shooting in after cleaning. Thirty or forty shots

have to be fired through the barrel before it settles down. The reason is a

failing barrel: the surface of the metal has deteriorated and requires "plating"

before the rifle will shoot. Sometimes such a barrel can be put right by expert

attention, but generally, it should be strongly suspected and too much money

should not be spent on it. Such a barrel may sometimes demonstrate the characteristics

of a leaded barrel, but to a lesser degree.

Fig.8 - Group Diagnosis (2) Ammunition

Unsuitable or poor ammunition. Note tight centre cluster and the few wild outside

shots.

Nearly all these target effects produced by a faulty rifle

are also capable of being produced by both ammunition and the marksman. TARGETS

should, therefore, be examined for more decisive evidence from one or both of

these sources before drastic action is taken.

The second factor-comparatively easy to assess-is the ammunition, which will

usually cause elongated patterns, that may not be always vertical, as might

be expected from velocity variations. This sometimes depends on the suitability

of a particular brand of ammunition in relation to bedding charac¬teristics.

The easiest way to check is to use ammunition of different velocity during tests.

Diagnosis is usually easier to make if the "feel" of recoil is coupled

with results on the target, but experience is necessary in interpreting such

short term indications.

Fig.9 - Group Diagnosis (3) The Rifleman

I) - Unsettled fore-hand position.

11) - Trigger Pulling.

III) - Pushing the butt forward with the shoulder.

IV) - Poor aiming-variable hold or inefficient sights or sighting.

The marksman factor is a much wider field of speculation. As a rough guide, large circular patterns can be traced to a marksman's poor aiming and to bad selection of sight apertures. Good central groups with occasional flyers are often caused by changes in hold or position. The effects of trigger pulling, and bounce on the forehand have been noted already, but there are other symptoms as shown in the accompanying illustrations.

Diagnosis of group patterns may not be so obvious as may be assumed from the foregoing, but there are savers or methods by which the picture can be clarified before an actual diagnosis is made. For example, in high-level shooting, where rifle and ammunition are normally likely to have been efficiently selected by the marksman, deviations can almost certainly be ascribed to him. Except for TARGETS shot by the veriest beginner, the rifle-ammunition characteristics usually predominate inside the group. Therefore the outside departures are the only shots that need investigation.

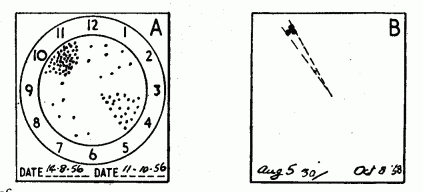

Fig.10 - Group Diagnosis (4)

Distribution of shots in the centre is due to chance and is therefore not capable of diagnosis. Only shots outside are subject.

Shots that hit the centre can be ignored, they have scored their maximum number

of points. As the pattern inside the ring is of no consequence and the position

of the shots purely a "chance" arrangement, these too, are of no interest.

The number of departures on a single target, even for a medium ability shooter,

is however, small and usually quite inadequate to give a true indication of

shooting faults. It is necessary to examine a large number of TARGETS

and to

make the diagnosis from a continuous record spread over a long period. Records

from less than about twenty TARGETS

are not of much value. Long term records

will clearly show the marksman's outstanding errors and these, when eliminated,

will leave evidence of finer details from which further diagnoses can be made.

To keep such records have a small piece of card and mark on it, immediately

after shooting, the positions of shots that fail to hit to the standard fixed

by the rifleman. It is unnecessary to record either the numerical value of the

shot or its distance from the centre; only the direction of the excursion should

interest the investigator. A shooting fault that puts a shot just out of the

ring is the same fault that puts it into the 8-ring. The type of error has to

be found, not its magnitude.

Standards of recording vary. The beginner will find it beneficial to start his

recording with all shots that do not make the 8-ring, at least, until he learns

to centralize the majority of his shots.

Fig.11 - Group Diagnosis (5)

The distance of a shot from the centre is not so important as its direction. A fault which puts a shot on the edge of the to-ring could, if only slightly more emphasised, have put it into the g or even the 8-ring.

The medium class club shot will need to record only the shots

that do not make the 10-ring. The expert will be interested only in those which

do not make the centre. These standards are not the same as the numerical evaluation

of them. The shots the marksman records could, by the laws of chance, have fallen

anywhere within the limits of the rifle¬ammunition group. Therefore, elaborate

records do not give any better diagnosis than rough guides.

If desired the clock-face can be drawn in on the record card, but in practice

this is not necessary. All that is needed is to establish which is the top,

12 o'clock, edge of the card, and the most convenient means of doing this is

always to write the date of the card in the same place-say, along the bottom

edge.

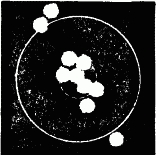

Fig.12 - Error Record Cards

A) - Indexed card for a beginner. It represents shots outside the 9-ring for his first twenty TARGETS over a period of ten weeks. It indicates trouble with the forehand (probably the sling) and pulling the trigger.

B) - Record for a marksman shooting to an average of 99.9 over thirty short-range cards. Again forehand trouble - when there is any!

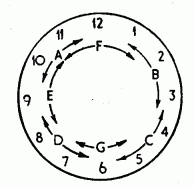

Fig.12a - Rapid Diagnosis Chart

Shot deflections into the angles covered by the arrows are likely to be caused by faults of the rifleman.

A) - Resting the fore-end towards the top of the palm or canting the rifle to the right.B) - Pressing the rifle over to the right to hold the sights on or canting the rifle to the left.

C) - Trigger pulling-which could include pulling back steadily with the hand.

D) - Forcing the shoulder on to the butt.

E) - Pressing the rifle over to the left to hold the sights on.

F) - Lifting the fore-end into the aiming-mark.

G) - Forcing the sights down.

The illustrations, Fig. 12, show the type of records likely to emerge. Record cards should be filed for future reference. A marksman may assume, that, having cured himself of a fault, it has been finally overcome. The fact is that he will always have a tendency to revert to it, and therefore, he should write on the record card what steps were taken to cure the fault.

The accompanying departure diagram can be referred to after the marksman has obtained a record from which a com¬parison can be made. The diagram covers faults that are most likely to be made by the marksman, but similar departures can be produced by faults in the rifle or in the ammunition or in both. It does not cover errors likely to arise from atmos¬pheric conditions, wind, mirage or changing light. These effects can normally be coupled with the shooter's normal senses and are additive to the general group patterns obtained under steady conditions. It is advisable not to include in the record cards departures made under adverse conditions unless they are so marked.

See also: Miniature Calibre Cartridges

Return to: TOP of PAGE

See this website's Raison d'être