See also: the 1916 SHORT MAGAZINE LEE-ENFIELD with ANTI-AIRCRAFT SIGHTS

As witnessed by the extracts from contemporary reports of operations in the early months of the Great War (1914-1918), later shown on this page, the lack of armament aboard those aircraft which the Royal Flying Corps then had available resulted in crews carrying their personal weapons; side-arms in the form of pistols - either revolvers or early semi-automatics, rifles and shotguns.

One report makes it quite clear that the earliest aircraft in use in WW1 were barely capable of taking the crew aloft, let alone any armament. The additional weight of a land-based Vickers Maxim machine gun brought the climb rate down to a truly dangerous level.

Whilst the first meetings of what were then considered merely reconnaisance aircraft of the belligerents were on an almost gentlemanly basis, it soon became apparent that something needed to be done to prevent the opposition from obtaining the information gained during such sorties, or at least preventing it from being returned to base. Initial attempts to shoot down enemy aircraft with pistols were rarely more than an effort to dissuade the opposition from further overflight. A rifle was a far better proposition, or even a large-calibre shotgun with especially made chain-shot loads.

For the pilot of a single-seat aircraft to use a rifle was barely practicable, but a double-crewed aircraft with an observer/photographer on board was a different matter. A rifle was a sensible option, and, if informally mounted, became a genuine threat to an enemy aircraft, bearing in mind the comparatively low speeds of operation at the time. Additionally, explosive ammunition had already been developed by Pomeroy for use in the otherwise long obsolete falling-block-action Martini-Henry single-shot rifles (of Zulu Wars fame) in early attempts to down hydrogen-filled dirigibles; Zeppelins and observation balloons being the number one targets.

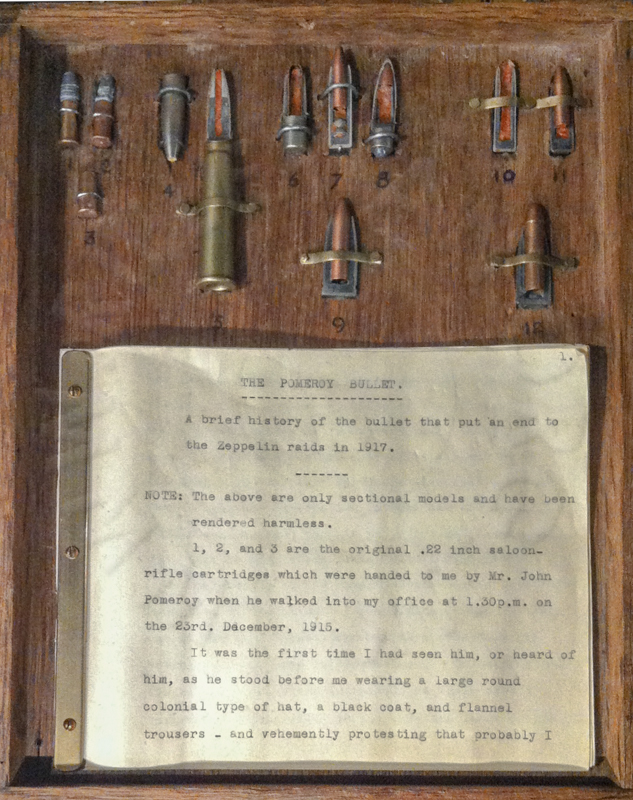

A display board of plain and sectioned bullets and cartridges, with notes on a brief history of the Pomeroy bullet.

Should you have access to the complete document we would be grateful to hear.

A flip-page booklet below offers an insight into Pomeroy's work, with a report of a 1908 trial in New Zealand reprinted after a cable to that country during WW1 commented on the success of Pomeroy's ammunition used against marauding Zeppelins.

This is followed up by detail of the Pomeroy round researched by the late Tony Edwards who, whilst still alive, was particularly helpful with the provision of material for the Rifleman site.

Tony's original site "Britmilammo" has been incorporated with the research of Peter Labbet by Richard Tordoff HERE

There was a 1916 design of .303CF incendiary round by John Buckingham, who had also produced a .450-inch Martini-Henry round. The .303 cartridge utilised a bullet filled with phosphorous, which ignites on contact with air. The bullet had a small hole near the base on one side; the hole was blocked with soft solder, maintaining a seal to contain the phosphorus. When fired, the heat developed in the barrel melted the solder and assisted in the ignition of the phosphorus, which was driven out of the hole by the centripetal force of the spin imparted to the bullet by the rifling. The bullet would emit a smoke trail for up to a thousand yards.

The most successful use of equivalent ammunition involved the Brock round which too was an incendiary type, the designer being a family member of the manufacturer of the famous Brock fireworks that many of us may remember from only two or three decades later.

We will, for a moment, jump somewhat ahead in the story, to mention the aerial employment of the Lewis light machine gun using these explosive and incendiary rounds, bearing in mind that a Lewis gun had first been trialled in the air at Bisley in 1913, using a Grahame-White aeroplane flown by Marcus Manton, with a Belgian Lieutenant firing from an improvised seat.

A reasonable level of success was achieved firing from 500 feet at a white sheet in a tricky wind, with 11 hits out of the first 14 rounds fired. In calmer conditions later, a full magazine was fired with "excellent practice".

Early in the War it had been already been discovered in experiments that explosive rounds would pass straight through the hydrogen filled gas bags of a Zeppelin without igniting the gas. This even proved to be true of the phosphorus emitting incendiary rounds. It was apparent that there was insufficient oxygen taken in with the bullet to encourage the hydrogen to ignite. The answer was found in combining the incendiary and explosive rounds alternately in the magazine of an upward firing Lewis gun mounted on a BE2C bi-plane. The explosive rounds opened up sufficiently large apertures in the gas bags to admit air in a quantity that allowed the incendiary bullet to do its work.

The first successful downing of a Zeppelin was achieved by Lieutenant William Leefe-Robinson over North London on the night of 2nd./3rd. September 1916. He raked the underside of the length of the airship twice, each time using an entire magazine. However, these failed runs changed his tactic, and his third and last magazine was fired into a concentrated area in the after quarter of the fuselage, finally succeeding in igniting the hydrogen.

Having braved the return fire from the Zeppelin, and the anti-aircraft fire from gunners below unaware of his presence, he was awarded the Victoria Cross. Such flying was in itself tremendously dangerous even without combat, being the earliest night-flying patrol work; altthough of course air-to-air fighting added to this significantly. At this point during home defence in the war, more pilots were killed or injured landing in the dark with primitive airfield lighting than were lost to direct combat.

Sir Richard Threlfall also designed a .303-inch calibre bullet, approved late in 1917, that used an explosive charge which combined phosphorus with nitro-glycerine to disperse the included incendiary compound on detonation.

Leefe-Robinson's own report on his sortie is related below.

_________

Returning to the main theme of this article, the general situation regarding the arming of aircrew with personal weapons, rather than providing aircraft-mounted arms, held sway until light-weight machine guns became available in sufficient numbers for adequate provision to the air force. The discovery that the Lewis gun could be adequately cooled by the airflow over an aircraft, thus permitting the removal of its cooling jacket with the commensurate weight saving, brought both attack by, and defence of, allied aircraft to a far more satisfactory level for the aircraft crews; particularly until more powerful attack fighter aircraft were brought into play, with the capability of easily raising a pair of machine guns into the air. However, until then, it was a case of 'needs must when the Devil drives'.

Below are rotatable Images of a Lee-Enfield Mark 1* - "Long Lee" - that has been shortened in the butt and fitted with a swivelling mounting bracket to locate in a mount on the cockpit side of an aircraft, probably of the observer's position. The mount swivels both in the horizontal ( in the aircraft mount) and vertical plane (on the rifle's mount) [obviously relative to an aircraft on the ground] but also has a hinge-like pivot, longitudinal to the rifle, that would allow the rifle to be rocked left and right, presumably affording the shooter the greatest flexibility in aiming.

The next two Images can be rotated and zoomed, either as initially loaded or full-screen for higher definition.

The rifle has been heavily coated with a now hardened shiny layer of what may possibly be castor oil, on top of its original linseed oil finish, perhaps stemming from the lubrication of an aircraft's rotary engine, which units operated on a total-loss oil system that caused the slipstream to deposit spent lubricant over the aircraft - and the crew - during flight. This suggests that the rifle may at some time have been used on a 'tractor' aeroplane such as a BE2 rather than a 'pusher' aircraft which, with its rear mounted engine and propellor would not have left lubricant much forward of the engine.

Beneath is a full-length rifle for comparison.

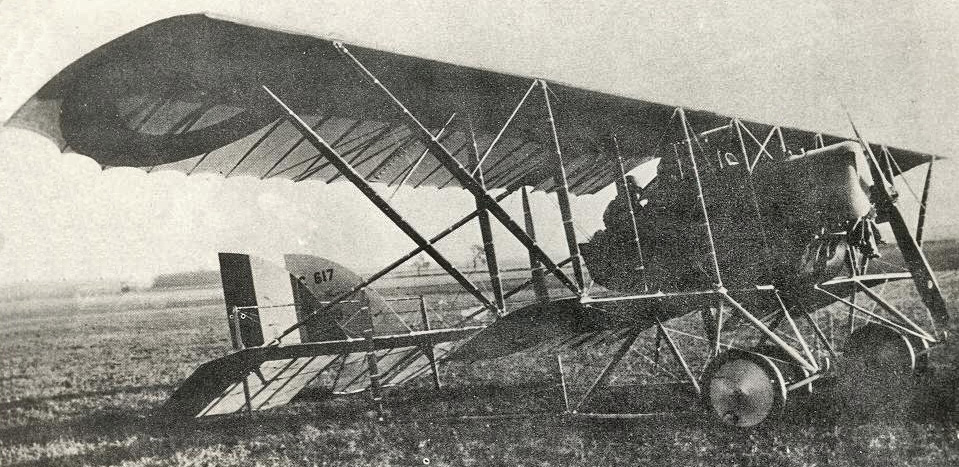

On the BE2, the observer sat in the front cockpit, rendering fitment of any gun mounting problematic, although far from impossible. But a rifle could be carried, if unwieldy in use - and with a limited view and risky aspect in the aim. A Lewis gun was eventually mounted aft of the observer's cockpit, with a field of fire aft over the pilot's head. Lateral firing was distinctly tricky.

At

Farnborough on the 6th August Lt. Geoffrey de Havilland, later a famous aircraft designer and manufacturer, demonstrated how to drop

bombs and fire a rifle from an aircraft.

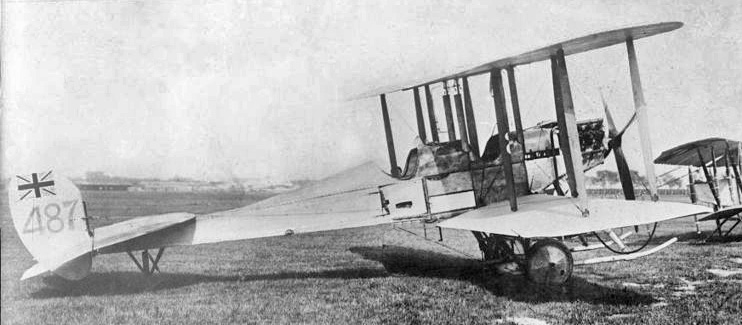

Of the aircraft in use by the R.F.C. early in the Great War, and derivative of the Farman HF20, the De Havilland DH.1 was produced by Airco (The Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited), which company was started in 1912 at Hendon, near the current home of the Royal Air Force Museum. Geoffrey De Havilland was working at the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough, but transferred to Airco as Chief Designer. He was responsible for many important aircraft throughout two wars, but initially the following D.H.2 design, a more powerful and capable reconnaissance aircraft of the 1914-15 period of the war, prior to the development of true WW1 fighter aircraft for attacking enemy planes, observation balloons and troops, as well as protecting the allies' observation aircraft on their own reconnaissance flights.

The DH.1 above, had the observer's cockpit of the earlier marque moved in front of the pilot and extended, to give far better vision around the aircraft, and lowered to afford better vision for the pilot. A Graflex camera could more conveniently be mounted outside the observer's cockpit on the side of the aircraft, and additional space was made available for the wielding of weaponry. At this stage, probably only personal weapons were carried, but, prior to the later fitment of a Lewis gun as engine output was increased, a mounted rifle was a distinct possibilty. A significant document relating circumstances at the time was the 'Wartime Diary of Major William Read'. This told of a number of operational situations, and some extracts have been used to illustrate points detailing the subject of this page. The general difficulties in flying, and the poor reliability of the machinery are quite apparent. In mid August 1914 Lt. W. R. Read was a

pilot in the fledgling Royal Flying Corps. In the early days of August 1914

the Corps was ordered to transport its force of 63 planes to France and

provide reconnaissance of enemy troop movements. Read kept a diary of his

experiences and we join his story as he and his observer - Jackson - fly over

the area of Mons, Belgium. Throughout his narrative, Lt. Read refers to his

plane as "Henri". William Read, at that time as pilot, relates ...... One day, after

our reconnaissance over Mons and Charleroi, Jackson spotted a German Taube

machine. I had also seen him but we had done our job and I did not want a

fight. Jackson was always bloodthirsty, however, and the following shouted

conversation ensued:

Jackson:

'Look, old boy!'

Me: 'Yes,

I know.’

Jackson:

‘I think we ought to go for him, old boy.’

Me: 'Better

get home with your report.'

Jackson: 'I

think we ought to go for him, old boy.'

Me: 'All

right.' "

"I changed

course for him and, as we passed the Taube, Jackson got in two shots with the

rifle. We turned and passed each other again with no obvious result. This

happened three or four times. Then, ‘Have you got a revolver, old boy? My

ammunition's all gone.’ I, feeling rather sick of the proceedings, said ‘Yes.

But no ammo.’ ‘Give it to me, old boy, and this time fly past him as close as

you can.’ I carried out instructions and, to my amazement, as soon as we got

opposite the Taube, Jackson, with my Army issue revolver grasped by the

barrel, threw it at the Taube's propeller. Of course it missed and then,

honour satisfied, we turned for home.

An Henri-Farman F20 observation aircraft similar to that flown by Lt. Read. He unsurprisingly called his

aircraft "Henri"

The next excerpt well illustrates the poor load carrying capacity of these aircraft before more powerful engines were developed and installed. On the 22nd. of August 1914 an

early attempt to get a Lewis gun into action in air-to-air combat failed when a

Royal Flying Corps Farman armed with one scrambled to intercept a German Albatros and took 30 minutes to climb to 1,000 feet, with the lack of performance blamed on the gun's weight. On landing, the pilot was ordered

to remove the Lewis gun and carry a rifle on future missions. The HF20 had, at the time, a usual maximum ceiling of about 6,000 feet. Other contemporary aircraft were little more capable. When the Royal Flying Corps was mustered to go to France

the BE2s of Nos. 2 and 4 Squadrons had no provision for armament other than a

rifle or the officers' side-arms. The Avro 504s and

BE8s of No. 5 Squadron were similarly unarmed and it appears that only the Henry

Farman HF20s of Nos. 3 and 5 Squadrons carried gun mountings. Nonetheless, some aircraft had been almost experimentally fitted with the lightest machine-gun then available; although many aircrew were still flying with just their rifles and pistols. Another contemporary book was "Recollections of an Airman" by L.A. Strange. Louis

Strange described his attempt to intercept a German aeroplane on 22nd. August 1914 with a Lewis gun fitted to his Farman, which was the only machine to have such a gun.

Nonetheless some other weapons were available, for on page 77 he mentions a flight on 1st. November 1914 in which he "chased a German machine for forty minutes and fired fifty rounds from a

Maxim". Similarly, a contemporary painting by a war artist depicts an Henri-Farman with a Colt-Browning mounted in the nose. The paucity of machine-gun-armed aircraft was shown by the fact that ...... At the beginning of the war the Royal Naval Air Service

possessed only two aeroplanes armed with guns and

both were based at Eastchurch. One mounted a Lewis,

the other a Maxim, and in addition one airship carried a Hotchkiss.

Significantly, the Lewis was on loan to the Admiralty from Col. Lucas of

Holland Hall, Yarmouth; ten months tater the Admiralty was still complaining bitterly that the allocation of Lewis guns to the RNAS was totally inadequate. When the RFC and RNAS went to war their principal weapons apart from various missiles, were hand-guns. The most widely available was the Army's Short Lee-Enfield rifle in the standard 0.303in calibre; known as the SMLE (Short, Magazine, Lee-Enfield), it had been approved on 23rd. December 1902 as the replacement for the Magazine Lee-Metford and the Magazine Lee‑Enfield (the 'long' rifle). The Mk. III was approved in 1907; the Mk. IV, a conversion

of older marks, was similar to the Mk. III and with the new Mk. VII ammunition

had an effective range of 800yds. Pistols were obviously of very limited use in those days, despite recorded use of Mauser C96 semi-automatic pistols by some German pilots, and another notable photograph extant of a Hungarian pilot with six of these Mausers mounted on his cockpit-side in a frame that permitted the firing of the whole battery with the pulling of a single trigger; Ingenious, but still with only very short range capability. But the use of rifles was still commonplace, and the Lee-Enfield figured notably in this respect, however, as previously mentioned, shotguns were an option, although these were suitable only for incredibly close-quarter use. Some early aeroplane weapons available to British crews, are shown in the image below.

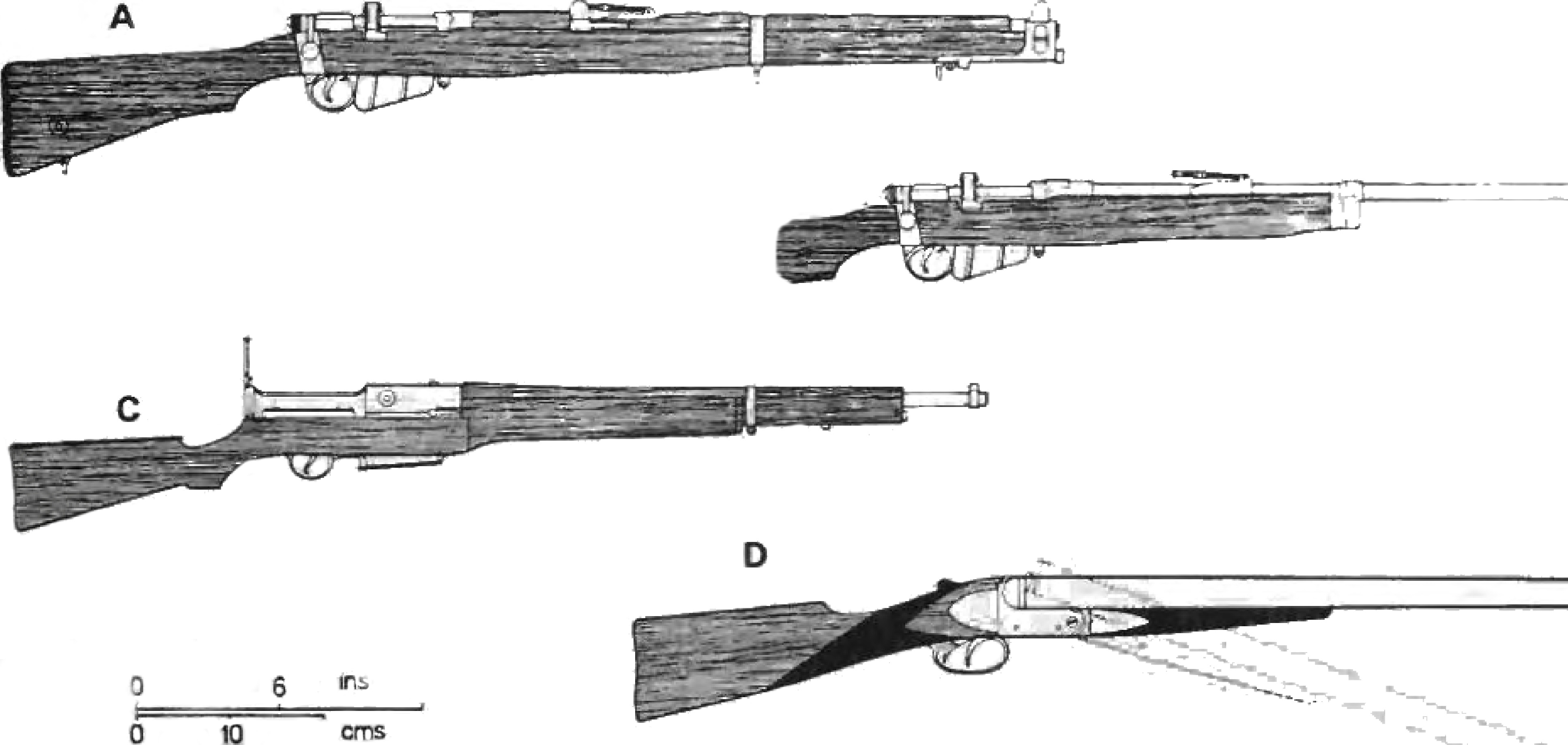

A.

The standard-issue Short

Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) rifle.

B.

One known example of a stripped rifle (such as that illustrated on this page).

C.

The Farquhar-Hill automatic rifle, one of a range available and issued.

D.

A Holland & Holland twin-barrelled 12-bore

'Aero' shotgun. Such

sporting guns had little practical value as apart from their unwieldiness they

had to be broken to be loaded - not easy in an aeroplane of the time. The Aero was available to RNAS crews as an anti-Zeppelin weapon.

To supplement these a variety of sports rifles and guns were available. Typical, and listed in RNAS armament inventories, was the Farquhar-Hill automatic rifle, a gas-operated self-loading rifle which could be fired either automatically (one press of the trigger and it fired continuously until the magazine was exhausted) or by hand (single-shot firing). The other weapons were game or duck guns and the preferred types were the Holland 12-bore of the 'Paradox' and 'Aero' patterns. These formidable (and costly) guns fired either buckshot or chain-shot and were later able to fire 'incendiary shells', i.e. phosphorous-filled shells (also known in contemporary literature as 'flaming bullets'), which were optimisticallv issued for use against airships. Another gun listed in RNAS CB1161 was the Remington 0.44 inch calibre rifle which could carry eleven rounds in its special chamber and weighed 71b when empty.

As is mentioned in the next extract, a number of pistols were in use in this early period.

Whilst revolvers were standard issue, allowing six-rounds to be fired before the necessary and tricky reloading in the air,

A Webley WG revolver - a private purchase similar to the Service Webley pistol.

they could only be fired either 'double-action' (with the commensurate difficulty in maintaining aim due to the high trigger pressure and longer trigger travel required), or by thumb-cocking between shots. The time this all took in the air usually that meant your target had passed by before many shots could be fired.

The U.S. Army Air Service Aircraft Armament Manual of WW1 carried the following notes:

COLT AND SMITH & WESSON REVOLVERS, CALIBER .45.

The Colt and Smith & Wesson revolvers have been made to handle the .45 caliber automatic-pistol ammunition. They may be used either as single or double action guns and each holds six rounds. In order to facilitate loading and ejection the cartridges are held in spring tempered steel clips each contain three cartridges, thereby making it possible to load the gun with two clips of cartridges. The clips are expendable and are ejected holding the empty shells.. A shoulder in each chamber prevents the cartridges from dropping through when placed in the gun without the clips. In case this is done, however, it will be necessary to pull the empty shell out of the chambers, since there is no rim for the ejector to force against.

It should be remembered that the cylinder on the Colt revolver rotates in a clockwise direction, and that on the Smith & Wesson in a counterclockwise direction.

The employment of semi-automatic pistols was a far better proposition. One of the earliest options was the Webley-Fosbery; still a revolver, but with a frame slide design by Colonel Fosbery that, when fired, caused a rearward movement of the barrel and cylinder that simultaneously indexed the cylinder to the next chamber, permitting semi-automatic fire, albeit still with only a six-round capacity. The use of the Prideaux quick-loading device could speed the reloading of any similar revolver, but was never as efficient as the magazine of such automatic pitols of Colt's design.

Click the image below for a slow-motion video clip of the Webley Fosbery in action.

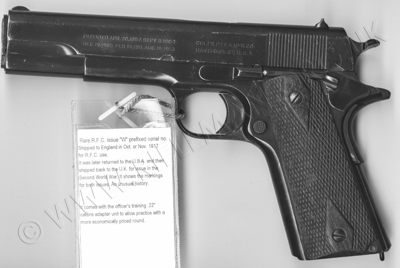

The U.S. Colt 1911 semi-automatic pistol was used by R.F.C. aircrew, some of whom were anyway North Americans, either U.S. citizens who joined the allied forces of their own volition before the United States became directly involved in the war, or Canadians who either had done the same, or were already in the Canadian Military.

Such pistols as the Colt 1911 had initially to be an officer's private purchase, although batches were purchased directly from Colt's later in the war.

As written in the extracted section below, all these pistols had to be of British Service calibre to ensure the availabilty and uniformity of ammunition supply.

A "W" serial prefixed Colt Model 1911 as issued to the R.F.C later in the War, but in earlier use as private purchases.

The U.S. Colt 1911, produced in its home country in .45 Colt Automatic calibre, was specially manufactured for the British Forces in their own .455 inch calibre, although for the 1911 this had to be a cartridge of rimless design rather than the rimmed case used in the standard issue Webley revolvers of the day.

Webley & Scott automatics were also used, and some were standard Naval issue, so likely to be found in the hands of R.N.A.S. aircrew.

Available side-arms w ere the 0.455in calibre Webley Fosbery pistol and the Webley standard service revolver, together with the 0.455in Webley and Scott self-loading pistols; in fact Army regulations laid down that an officer could use any make of pistol provided it could accept the standard cordite pistol cartridge of 0.455in calibre. In practice this meant that Webleys, Colt Pistols, Smith & Wessons and Webley-Wilkinsons were issued and used, although other guns such as Mausers were also in circulation. Rifles were carried in aeroplanes well into the war, even after machine guns became available: the Lee‑Enfield for example was frequently stripped down like the Lewis gun. One of the stalwarts of the RNAS in 1914 was Maj. E. L. Gerrard RMLI, who in 1920 (as Gp. Capt. E. L. Gerrard CMG DSO) compiled some notes for the Air Historical Branch of the Air Ministry. Some of his comments about the early days at Eastchurch from November 1914 to May 1915 are of particular interest in relation to early armament: Aerial gunnery was obviously about to become of greater importance. The first machine we had in which the armament formed part of the design was the Vickers gunbus. It was a steel 'pusher' with only a 100hp Gnome engine. It was unpopular among pilots for various reasons. It was heavy and gave insufficient climb when fully loaded with full tanks, a maxim [sic] and a crew of two. It was also sluggish and heavy on the controls, especially the rudder. It was eventually crashed by Warrant Officer Alcock [later to be first to fly the Atlantic Ocean with Lt. Brown in a twin-engined Vickers Vimy bomber; Ed.]. The earliest armament was probably the twelve bore gun carried in the Blériot Parasol. It was mounted upon the starboard plane and inclined to the aft of the machine so as to clear the propeller tips. Chain shot ammunition was used, small lead balls connected by a short length of steel cable. Both hands were required to reload both barrels - a difficult operation in a non-stable machine. The range was short and accurate shooting very difficult to obtain. We never obtained any results with it in service.

Whilst there are many recorded instances of pistols being used to fire at enemy aircraft, it should be borne in mind that the use of these pistols was rather more intended as side-arms, carried by the aircrew for personal protection if evading troops in enemy territory after a forced landing,

but with the idea always in mind that, if attacked in the air, and with an aircraft burning or otherwise no longer capable of flight, a certain end could be precipitated by use of their pistol, rather than suffering a protracted leap to death from many thousands of feet up.

From the book of WW1 letters to his wife - "No Parachute", by Arthur Gould Lee, we show two excerpts, the first of which is dated Wednesday 13th. July 1917.

Lee, then not yet 23 years of age, wrote of the Colt automatic pistol each of the Sopwith Pup scout pilots carried in their cockpit. His young wife asked the reason, and Lee afforded an insight into the uses to which such pistols could be, and, in a following more light-hearted missive, were put.

Today’s query from home - why do I carry a Colt in the cockpit? For the reason we all do. Not to stage a one-man battle against a platoon of Boche soldiery if forced down the other side—I’d be butchered instantly. No, it’s the fear of being set alight. It’s something nobody talks about, but it’s at the back of everybody’s mind, and each of us knows he couldn’t take it. To be burned alive, however soon it’s over, is the one thing we can’t face. Better to use the gun and end it in a split second.

Thursday, June 14th

You ask me why we carry an automatic in the cockpit. Well, it’s not to use in a dog-fight when the Vickers packs up, though pilots have been known to try a shot. It’s officially to protect yourself if you have to forced-land in Hunland, though I can’t see anybody getting far with that. What they’re most useful for is killing frogs.

The latter remark refers to the fact that there was a large pond, adjacent to their makeshift accommodation on the aerodrome, which pond was heavily inhabited by a large colony of frogs that were particularly noisily croaking when the pilots were trying to sleep at night. One of the crews' pastimes between patrols was to use the frogs for target practice with their Colts - probably the imported 1911 models issued to RFC aircrew in 1917, although some carried revolvers.

The Vickers pusher aircraft referred to so disparagingly by Gerrard was one of six pre-production FB5s which had been delivered just before the war and taken over bythe RNAS at Eastchurch September 1914. Four others were at Farnborough by early October, for on the 6th. of that month Section MA2 of the War Office wrote to the Chief Inspector of Small Arms at Enfield Lock asking him to expedite the testing of the Vickers guns earmarked for the machines as soon as possible. The CISA replied by telegram the following day: 'Six 0.303 inch Maxim guns with pivot mounting and parallel motion sights are being sent to the Officer Commanding RFC South Farnborough by passenger train tonight. The spare 10 locks will be sent tomorrow.'

A mounting scheme for a Holland & Holland shotgun on a Sopwith Schneider, from an RNAS drawing: dated July 1916.

The subject of this page may be the use of rifles in aircraft in the early part of WW1, but the work done to replace such firearms with more effective weaponry is worthy of mention.

The main manufacturer of the Lewis gun was the Birmingham Small Arms Company, and the author writes of the award of the contract for production of these arms to that company as follows.

From the national point of view it seems also providential that the manufacture of the Lewis Gun fell into the hands of the B.S.A. Company, for when the war opened and machine guns were found to be required in enormous quantities, here was a wonderful weapon, fully worked out in all its details and comprehensively planned to promote straightforward conditions of manufacture. Of the six pre-production Vickers Fighting Biplanes delivered it seems probable that the five taken by the RFC were all fitted with the fixed pillar mounting in the nose, the pillar being contained in a streamlined fairing.

That some pilots and observers had made their own arrangements for supporting rifles and pistols on their aircraft to improve their effectiveness will no doubt have had a bearing on the subsequent designs for mounting light machine-guns in a similar way.

When the mountings were later classified by type the version became known as the 'No. 1

Mk II (Plane pedestal for elevation and traverse with clamping screws)'. The

Vickers taken over by the RNA S, serial no.32, is depicted in at least two

photographs in which the nose of the nacelle is shortened, i.e. it does nut

have the wedge-shaped form of the RFC machines but is similar to the shape

eventually adopted for the productiion models: in

addition the upper rim of the gunner's cockpit consisted of a half-ring

structure (actually a pressed steel track) and the gun mount was seen to be

behind the front lip of this half-ring. This fitting, after some modification was later given the classiffication 'No. 2 Mk. I (On semi-circular travelling rail, clamp for elevation, traverse and travel. Handwheel for rotating)'. The mount was originally designed for the Vickers gun, but when the Lewis became available in earlv 1915 it was subjected to field modification in squadron workshops.

Whilst it appeared that the rail and wheel mounting were designed for the Vickers, the method of traverse and the hand wheel operation had a distinctly naval connotation and it is quite possible that it was conceived or

suggested by the Admiralty Air Department, an office that would be responsible

for many good ideas in the field of aircraft armament. This brief account of

the metamorphosis of the Vickers gun mounting in the FB5 serves to illustrate that even

at the very beginning of the war constant alterations and improvements were

common.

On 24th. November 1914 it was decided to arm the Vickers FB5 with the Lewis,

which was now regarded as the ideal aeroplane weapon

(particularly by the field units), but not enough were available: it was not

until mid-1915 that the shortage would be to some extent rectified and

consequently early FB5s usually carried Vickers guns. However, even Vickers

guns were not easily obtainable. As mentioned earlier, the Vickers production

facilities were still no more than were required for peacetime production, and

in August 1914 the company could only produce 10-12 guns a week;

indeed when war broke out only 100 guns had been delivered. One week after the

declaration of war on 5th. August the War Office ordered 192 Vickers guns, sufficient

to equip the six divisions of the British Expeditionary Force as originally

planned. By September things began to look rather _different and the order was dramatically increased.The French Grand Quartier Géneral,

in common with its

The British were not the only aviators in the unenviable positon of being unable to satisfactorily defend themselves from the burgeoning attack capabilities of the more powerful of German aircraft.

The French too were of necessity resorting to personal weapons to dissuade enemy reconnassance in the air.

The period from the beginning of the war until mid‑1915 is known to French historians as Le Temps- des Carabines — the Time of the Carbines. French airmen had quite a selection of weapons to choose from provided that they were available. As side-arms, they had and could use the standard military weapons such as the 8mm modèle 1892 revolver or the 11mm modèle revolver, in addition to various automatic pistols obtained from several sources.

Somewhat more effective were rifles, carbines and automatic firearms. The basic French infantry rifle was the 8mm modèle 1886 Lebel (modified in 1893) or the newer Fusil d'Infanterie modèle 1907, also in the standard 8mm calibre. Easier to handle in aeroplanes were the shorter‑barrelled carbines such as the Carabine de Cavalerie modèle 1886-90 or the 'Musketoon' (Mousketon d'Artillerie) modèle 1892. Other favoured weapons were the Remington single-shot rifle of 1914 or the 1906 model repeater rifle, but best of all were automatic rifles such as the 1906 Browning and any others that could be obtained by purchase.

On particularly popular model, and officially issued, was the Winchester Model 1907, the big brother of the little .22WCF Model 1903.

Again, the U.S. Army Air Service Aircraft Armament Manual of WW1 carried the following relevant notes:

WINCHESTER RIFLE, CALIBER .351.

The Winchester self-loading rifle, caliber .351, is some- times used as an auxiliary weapon in aircraft. The action of the gun is semi-automatic as the name implies and it is fed from a detachable box magazine holding five Cartridges. One cartridge may also be carried in the chamber, giving a total of six shots.

The magazine is removed by releasing the magazine catch which extends from the lower edge of the right-hand side of the receiver, and is then loaded and replaced in the gun.

The first cartridge is then fed into the chamber by pressing in on the rod extending from the forward end of the forearm. The gun will now fire every time the trigger is pulled until the magazine is empty.

The safety consists of a small pin located in the forward part of the trigger guard. The gun is safe when the safety extends out from the right-hand side of the guard, and is made ready to fire by pressing the safety to the left.

Later in the war, and half way between semi-automatic rifles and machine guns, another U.S. option lay with the newly introduced Browning Automatic Rifle - Model of 1918. The BAR as it became widely known, particularly when it was reissued to the British Home Guard in the Second World War, was provided to WWI aircrew as a supplementary weapon. The U.S. Manual entry read ........

BROWNING MACHINE RIFLE.

DESCRIPTION.

The Browning machine rifle, model 1918, is a light automatic chambered for United States standard .30 caliber ammunition. It weighs 15 pounds 8 ounces and has a rate of fire of approximately 500 shots per minute. It is a gas-operated gun and may be fired automatically or semi- automatically. The gun is fed from a magazine holding 20 or 40 rounds fitted underneath the receiver, just in front of the trigger guard. The automatic action of this gun is not disturbed by holding it in any position whatever. No tools are required for dismounting and assembling of the rifle unless.* is desired to remove the barrel and gas cylinder, which necessitates the use of a special spanner provided in the kit. Ordnance handbook No. 1934 describes this rifle in detail.

USE.

This rifle may be carried as extra armament in case of emergency, or may be mounted on the flexible ring mount as a single or double flexible gun.

POINTS TO BE OBSERVED BEFORE A FLIGHT.

1. Thoroughly inspect the gun for defective or worn parts and replace all such parts with new ones.

2. Always carry gun in safety.

3. See that all magazines are fully loaded and in proper shape.

4. See that all working parts are covered with a thin film of oil.

5. See that gas cylinder has its proper setting.

6. See that recoil spring has not set so as to be too weak to operate the gun.

7. Be sure that magazine is all the way in and well fastened.

THE HOME GUARD TRAINING CHART FOR THE BAR

Some mention of allied work with light machine-guns is also justified, with the French use of the Hotchkiss matching that of the Lewis gun on British aircraft.

The author wrote interestingly on the subject as follows ..

On mobilization the French Army could field twenty one escadrilles equipped with nine different types of machine — Maurice and Henry Farmans, Voisins, Breguets, Caudrons, Bleriots, Deperdussins, REPS and Nieuports.

There were also two Escadrilles de Cavalerie, making a total of 132 aeroplanes. None of the machines was armed unless the pilot or passenger happened to carry small-arms. Despite the paucity of armament the first decisive victory by a French aeroplane over the enemy occurred on 5th. October when a bomber, a Voisin LA5 of V24 piloted by Sergent Joseph Frantz, attacked an Aviatik (serial no. B.114/14). Frantz's gunner was Mécanicien Louis Quenault, who was armed with a light Hotchkiss, and after a few bursts the Aviatik crashed to the ground in flames near Jonchery (Marne).

That the Voisin had a machine gun at all was due to the commander of V24, CapitaineFaure (who had decided that his machines would be armed) and to the audacity of Gabriel Voisin. According to Voisin's own account of the affair, the High Command was opposed to the arming of aircraft, so he went to the Mire de la Guerre to obtain the necessary authority for the delivery of twelve Hotchkiss guns with ammunition. He was received by General Bernard but was told that he could have nothing to do with arming the Voisins. Despite this rebuff he went to the Hotchkiss company at Saint-Denis and placed a formal order for twelve guns with magazines and ammunition. As he was about to leave he was asked for the authorization for the delivery so he wrote it out himself and signed it in the name of General Bernard. According to Voisin, 'I signed my name on the delivery chit and 24 hours after my arrival in Paris I was on the way to Mézières with my equipment in the vehicle'. Gunnery training at the squadron was simplified drastically, those who were mechanics being given a crash course in loading and aiming the guns: within an hour all had become 'gunners'.

The limited early wartime ability of British munitions manufacturers to keep up with demand caused difficulties between the allies.

French industry provided airframes and engines for the RNAS and the Service now found itself in a very embarrassing position for it could not meet the demand for more Lewis guns; the French, having been generous with equipment, could not understand this and became rather belligerent, threatening to cut off the supply of material to the RNAS unless their wishes were met. Eventually the matter was referred to Lord Kitchener, who ordered that Lewis guns be diverted to France. The immediate crisis was over and the increasing number of guns being produced eased the situation. However, by the end of 1915 no Lewis guns appeared to have trickled through to Wg. Cdr. C.R. Samson commanding No. 3 Wing at the Dardanelles: his orders of 4th. December 1915 stated that pilots were to be armed with a revolver or pistol and that observers should carry a rifle. It was not until the early months of 1916 that the Lewis became available in sufficient quantity; even so there occurred a temporary shortage of the modified Lewis (for air use) in August 1916 and for a while some ground weapons were pressed into action.

BSA had started limited production before the war and some deliveries had been made to the Belgian and Russian Armies — it was in Belgium in fact that the Germans first encountered the familiar staccato sound of the Lewis firing in short bursts, naming it the 'Belgian Rattlesnake' — but the company quickly realized that the demand for machine guns would increase enormously despite the modest orders from the War Office and the less than enthusiastic attitude of the British military establishment.

The British were in dire need of assistance with the provision of the huge quantities of munitions now evidently required to pursue the war.

The United States of America were at this time formally declared neutral, and the nation held a significant population of German and Austrian descent.

Despite considerable internal opposition to any American involvement whatsoever in the War,

President Woodrow Wilson, sympathetic to the Allied cause, was initially required to work somewhat behind the scenes to enable U.S. industry to do what was required.

Only after German belligerance in U.S. waters, and clandestine interference in politics and industry, was American public opinion directed against Axis activities.

To that end ...........

In 1914 the Savage Arms Corporation of Utica, New York, had obtained the exclusive manufacturing rights for Lewis guns in the Western Hemisphere and they soon received substantial orders from Europe, one of the first being a joint Canadian-British order for 12,500.

Throughout the war Col. Lewis (he had been promoted in 1913) spent a great deal of time in Britain; he was the technical director of Armes Automatiques and in this capacity he was responsible for many of the improvements and modifications to his gun. One of his earliest achievements had been to simplify some of its components for mass production and many of the subsequent improvements had their origins in suggestions made by members of the RFC and RNA; in the light of operational experience. Three French firearms used by airmen included the Fusil d'Infanterie, modèle 07/15 (Remington): the Mousqueton d'Artillerie, modèle 1892;and the Carabine de Cavalerie. modèle 1890.

The similarly fragile and low-powered early French reconnaissance aircraft, the Caudron GIII, was also initially armed only with personal weapons.

The Caudron GIII: image by courtesy of Fuerza Aérea Colombiana

The French Caudron GIII aircraft presented difficulties because the passenger sat in front of the pilot, in between the wings, and with little or no field of vision, let alone a field of fire. In some of these aircraft a light weapon such as a rifle was mounted so that the pilot could at least give the impression of being armed. The Caudrons, although tractors,(pulled by a propellor at the front) were to suffer in the same way as the pushers (pushed by a propellor at the rear of the engine and fuselage) in that they were all highly vulnerable to attack from the rear, especially when the armed German scouts appeared. The Nieuport 10 two-seat tractor biplane, the progenitor of a successful series, appeared at the end of 1914; here the gunner was again in the front but he was required to stand on his seat and fire through a large hole in the centre-section. This was eventually changed to a smaller hole, with the gun frequently fixed to fire diagonally upwards (an arrangement associated with the single seat version of the Nieuport 10 and one used on British and Russian Nieuports).

An incident involving the famous French flying ace Roland Garros, for whom the present-day Paris tennis facility is named, in a two-crewed Caudron was reported as follows ..

They did have some success and a number of the later French aces cut their teeth in them. Garros made his first operational flight on the 19th. August 1914 whilst with MS26: his observer carried a carbine and together they made an unsuccessful attack on an Euler. Two davs later, with another observer, he attacked an Albatros near Lunéville and the observer's gun jammed. Garros was, needless to say, frustrated. In November he was posted to Paris to enable him to have discussions with Raymond Saulnier about aircraft armament. Meanwhile some airmen were experiencing successes despite the paucity of machine guns. Navarre used his Mauser pistol whilst his companion had a mousqueton, and the Aviatik fell behind German lines.

It should also be remembered that rifles and shotguns in particular were much used in training aircrew in preparation for air-to-air combat. Pigeon and clay-pigeon shooting was much encouraged to assist in learning to "lead" a moving target. This was to help with the assessment of how far ahead it was necessary to shoot in front of anything fast-moving.

Indeed, both rifles and shotguns were provided on airfields to enable pilots and observers to gain experience of such shooting.

Even small-bore rifles proved useful, in that practice was possible cheaply and in restricted space. The British War Office purchased and imported Winchester Model 1903 semi-auto rifles and a huge quantity of the centre fire Winchester .22 ammunition for such purposes. A mounting for these rifles was even produced to permit short range "sub-calibre" practice with the Lewis gun.

In his fine book "Winged Warfare", Maj. W.A. Bishop V.C., D.S.C., M.C. vividly recounted his flying experiences throughout the First World War in Nieuport and SE5A aircraft, but he also described a number of off-duty times, including regular shooting events. One of these occasional activities very likely involved the issued rifles here discussed. He wrote:

" Another sport, and a very good one, was to take a 22-calibre rifle and try to shoot individual pigeons on the wing. It was a very hard thing to do and required much practice. Luckily we did not hit too often, as we paid well for each pigeon we shot down. I remember one afternoon firing 500 rounds and only hitting one pigeon, and I considered myself lucky to hit that one. This sport was much encouraged, as it was the very best practice in the world for the eye of a man whose business it is to fight mechanical birds in the air."

So effective was this type of training that, shortly after the War ended, specialist non-firing equipment was designed for training both ground troops and aircrew in anti-aircraft firing with small-arms. See the Flash Spotter rifle, and the Spotlight Projector devices designed for use with both the Lee-Enfield rifle and Lewis guns. Later attachments were even provided for the Thompson and Sten sub-machine guns; all to teach how to "lead" by 'shooting' at a model aircraft running along a wire set up in a training hall.

With further consideration of the Lewis gun, we should mention that this website's main purpose is as a reference facility for training rifles and equipment. Parker-Hale manufactured much of this equipment, including the Pattern '14 Lee-Enfield rifle in .22RF calibre, and other sub-calibre devices such as the Pattern '18 "303cum 22" Lee-Enfield rifles with their .303CF-cartridge-sized conveyor adapters to fire .22 rimfire ammunition on short practice ranges.

Equivalent adapters were available for the Enfield and Webley revolvers (also see Miniature Calibre Adapters), and a similar system was even made available for the Lewis light machine-gun.

Further detail on pistol adapters can be found on the page covering the A.G. and A.J.Parker, and Parker-Hale companies.

The potential threat posed by German airships was identifiesd well before war commenced, and Winston Churchill had already recommended the use of aircraft as a counter. Largely speaking, Zeppelins flew at heights above the ceiling of the early aircraft of WW1, but occasionaly approached London at lower altitudes to increase the accuracy of their bombing.

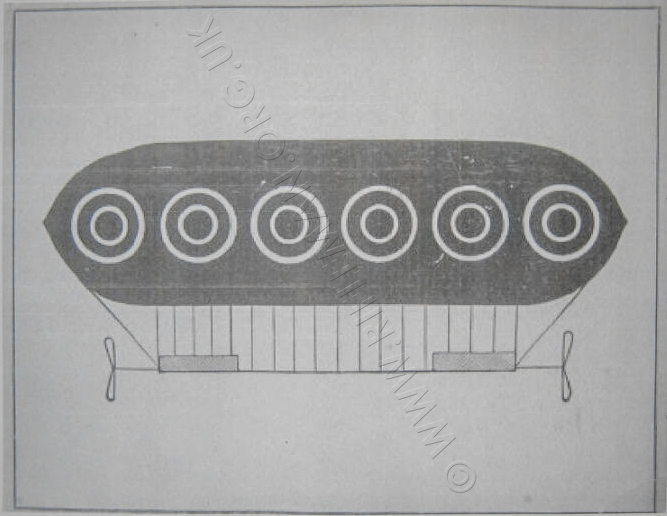

A novelty target of a Zeppelin for use on miniature rifle ranges

Early attacks by RFC aircraft served to prove the difficulty of doing other than puncture the enormous hydrogen-filled bags within the Zeppelin's outer envelope. (These bags were made of thousands of cows stomach linings carefully stitched together - leading to tight control of all cattle within German occupied territory). Hundreds of rounds of machine-gun ammunition would fail to ignite the otherwise highly flammable gas; even tracer failing to do so.

A means was required to puncture the gas-bags with a projectile that carried sufficient incendiary material to ensure ignition of the hydrogen, which seemed to stifle smaller incendiary bullets. Three designs were produced during the War, the Brock, the Buckingham and the Pomeroy. The Brock and Pomeroy ammunition was used, mainly in a later .303 inch calibre machine-gun type, througout the war, but the Pomeroy in its first guise is what brings it to our notice here. An early version of John Pomeroy's cartridge was in .577/.450 calibre, that of the Zulu War era Martini-Henry single-shot falling-block actioned cavalry carbines.

On the basis that any means of combatting the new menace needed to be tried, these rifles with their incendiary ammunition were borne aloft in the early period of the Great War. As with manifold other rapid advances in aircraft and weaponry, such methods were soon rendered obsolete by the use of the Lewis-gun with the .303" Brock and Pomeroy ammunition on board more powerful aircraft. The Lewis was preferred for this task, as the Vickers gun was found less suitable for the firing of this highly specialist ammunition.

A fascinating insight into the opposite side of the fence of the subject of this page - the use of the rifle in defence of attack from the air - is to be found in an article that was published in the journal of the National Rifle Association (Bisley, England) in December 1913, less than a year prior to the commencement of the Great War. The then novel addition of aircraft to the field of battle led to many varied opinions of how the use of them would either help or hinder any future combatants.

Many doubtful theories were put forward, particularly from senior members of the services competing for control of the new opportunities in aviation. Some ideas were frankly nonsensical, but others held great prescience. The article offers an idea of the problems being considered and argued over at the time.

AIRCRAFT AND THE RIFLE.

THE USES OF SMALL ARMS IN DEFENDING AGAINST AERIAL ATTACK.

'The art of flying is still in its infancy and already we have had some experience of the uses to which it may be put in warfare. Luring the progress of the war in the Near East, the flying man has shown that he is a force to be reckoned with, and that in the battles of the future attack will be by air as well as by land and sea. What is the role of the rifleman in the new condition of things? Is he to be considered a factor in. defence? Undoubtedly he is. And it is easy to predict that target practice and rifle shooting competitions will, in all probability, soon develop addtional interest in a new and. difficult test of marksmanship.

Although aerial craft are capable of attaining great heights, yet their use in warfare necessitates that they shall approach tolerably near to the earth if they are to be of any service. But such a statement requires qualification, when one considers separately the dirigible balloon and the aeroplane. The airship will be employed more particularly in the nature of an attacking force. 1t can carry large quantities of explosive material, and, as it can hover over a position for some length of time, it is able to drop its explosive burden more or less perpendicularly. The higher it is the less accurately can it make aim, and the lower it is the greater risk does it run of coming to grief by the explosion it has itself created, and the better target does it afford to the defender.

The aeroplane, on the other hand, will be most suitably employed for purposes of reconnaissance. Unlike the airship, it cannot hover; its support in the air is product of its own movement. And for observation, purposes it is necessary that the aeroplane shall not be at too great an altitude. Experience, limited as it may be, has already shown that observation is difficult at heights above three or four thousand feet. At such a range the aeroplane becomes a ready target for the infantry in the enemy's ranks. In the various journals devoted to ordnance and rifles and munitions of war generally, the subject of aerial attack and defence is being given considerable prominence just now.

Recent issues of the well-known English monthly, Arms and Explosives, have contained articles dealing with vertical shooting with the rifle, and some interesting details are given 'concerning the potentialities of the Mark VIII bullet in this connection. The first article, which appeared in the July number of the journal just mentioned, went into the historical details of experiments with vertically-fired bullets. One hundred and fifty years ago we find Benjamin Robins, out of mere curiosity, experimenting with a smooth-bore rifle, and recording the results of firing bullets in a nearly vertical position. Then came the well-known Dr. F. W. Mann, the American rifle experimentalist, who confessed that, although he fired eight bullets vertically, he was unable to detect their return to earth again. Following Dr. Mann's account of his unsuccessful experiments, there is detailed the experiences of Captain J. H. Hardcastle, late Royal Artillery, and Mr. L. R. Tippins, of Mistley, who were both successful in timing and locating the fall of perpendicularly-fired bullets. It is evident, however, that bullets fired at high angles of elevation are subject to the effects of currents of air blowing in haphazard fashion. Indeed, there would appear to be much of truth in the observation that "the employment of rifle fire at extreme elevations against an aerial enemy necessitates adequate protection for the infantry, especially when we remember how uncertain are the whereabouts of the falling bullet." The falling Mark VII bullet reaches the earth• with a striking energy of 86 foot-pounds, and-' as 60 foot-pounds are considered sufficient to put a living target out of action, we can see that there is ample reason for the warning.

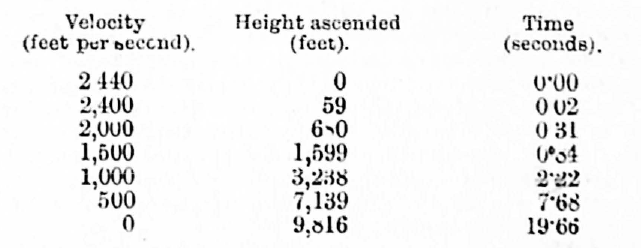

But the one interesting Feature of the subject is the figures concerning the Mark VII bullet, when fired vertically.

If we look at these figures we can gather some idea of the power of our service rifle when it is used in the defence against' aerial attack. The Mark VII. bullet has a muzzle velocity of 2.440 feet per second, and it weighs somewhere about one-fortieth of a pound, or to be exact, 174 grains. What this bullet is capable of vertically may be judged from the following table of figures, which is compiled from the available statistics:—

This table of statistics affords us not only some idea of what the Mark VII. bullet can do vertically, but also at high angles of elevation, such as, 70 degrees and 80 degrees, because at extreme elevations such as these the behaviour of the bullet is not a great deal, different to that when it is fired exactly in the perpendicular position. Considering the figures, we see that when a height of 59 feet is reached the bullet has lost 40 feet per second velocity. At 1,600 feet altitude the velocity of the bullet is 1,500 feet per second, and this height is reached in. less than a second oil time.

An aeroplane moving at this height at a speed of 50 miles an hour would have covered, but GO feet in the time taken. for the bullet to reach the height of the target. It should not, then, be a difficult thing to make due allowance on the rifle sight for the movement of an aerial body. It has already been said that the height at which an aeroplane would fly over an enemy's head, if the observers in it were to be advantageously situated to make observations of

a position, would be somewhere between, say, three or four thousand feet.

The table tells us that to reach a height of 3,200 feet the bullet takes 2 1-5 seconds, and has a remaining velocity of 1,000 feet per second, equivalent to a striking energy of 386 foot-pounds. We are able to estimate, then, the effect that rifle fire directed against an aeroplane must have upon the pilot. Marksmanship should' not prove so difficult as it might at first appear to be. Elevation on a high angle line of sight is less than on the horizontal plane against a terrestrial target. Again, with a two-second time of flight allowances for speed of targets should not he difficult.

The conclusion is that, assailed by rifle fire, the pilot of an aeroplane would, to say the least, spend a most unhappy time. The morale effect of rifle bullets whistling about his ears—for even if the noise of his engine were to make it impossible to detect the sound of passing bullets, it would hardly be loud enough to smother the noise created by a salvo of rifle fire—must indeed be enormous. Several hits on his planes would perhaps be of little consequence, but one or two in his propeller or in a vital part of his engine, or in his own anatomy, would spell instant disaster.

It is quite apparent, then, that in the defence against the new arm [the RFC: Ed] the rifle is to fill no small part. It can undoubtedly be used most effectively, and without any special training in firing against aerial targets, the infantryman would in all probability be of great service. With some practice at moving aerial targets he would rapidly become accustomed to the new conditions. The remaining interesting from in the table convey further facts from the theoretical point of view. We see that the Mark VII. bullet takes nearly 20 seconds to reach a height something short of two miles before it has lost all its upward velocity. The bullet takes 31 seconds to reach the ground again, where its velocity is only 473 feet per second, to compare with its initial upward velocity of 2,440 feet per second.

One invention for sighting a No.1 Lee-Enfield rifle against attacking aircraft was trialled in 1916.

It consisted of a celluloid square slid under the rifle barrel's tangent rear-sight.

The Small Arms Committee's minute on the subject is replicated below.

The device was considered too fragile for realistic use in the field.

Apropos one contemporary idea relating to the use of the rifle in defence against aeroplanes,

see: the SMLE with anti-aircraft sights.

or move on twenty odd years to the Second World War (1939-45) comprehensive Small Arms Training pamphlet No.6 on the anti-aircraft use of small arms, issued in 1942.

Recommended contemporary reading on Royal Flying Corps subjects would include;

The Wartime Diary of Major William Read - Private papers held by the Imperial War Museum.

Recollections of an Airman - L.A. Strange

"Early Aircraft Armament - The Aeroplane and the Gun up to 1918" by Harry Woodman - 1989

And a finely descriptive narrative of operations is 'Flying for France' by an American pilot with a French escadrille in 1915.

The latter two books, and many others relating to WW1 aviation, are freely available digitally from Archive.org

See also: the 1916 SHORT MAGAZINE LEE-ENFIELD with ANTI-AIRCRAFT SIGHTS

and more on Lee-Enfield training rifles